What is a ligament injury?

Ligaments are the tissues around joints that help stabilise the joint maximising strength and preventing excess movement. Ligaments are attached to the bones either side of a joint. Ligament injuries are very common especially in the hand as it is so exposed and so widely used in day to day activities. Ligament injuries are typically partial tear known as sprains. Most heal without any problems. Complete tears can occur and ligaments can be cut in accidents with sharp objects.

What do they look like?

Ligament injuries are often obvious because of local pain and swelling. The severity can easily be overlooked. We see many patients who come several weeks or months down the line from injury who had not appreciated the severity of the problem. At the later stages there is often less pain but instability i.e. excess/abnormal movement in the local joint.

How is the diagnosis made?

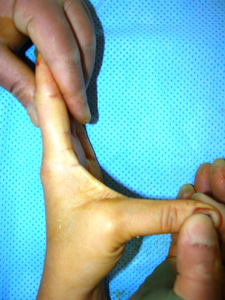

The Hand specialist who sees the patient will ask questions about their injury and in particular how it occurred. They will then examine the patient looking at the injured site. Stressing i.e. pushing on the affected area will be uncomfortable but is usually necessary to demonstrate some tenderness and possibly instability to confirm the site and scale of the symptoms but this should not be too painful.

What investigations (tests) are needed?

For the milder injuries no tests are needed. For most of the rest of the injuries X-rays will be performed. Most of the injuries show nothing on the X-rays. Sometimes a small fracture shows which does not need specific treatment over and above the ligament injury, rather it is a marker of the severity of the injury. If there is a large fracture fragment which can occur this is treated as a bone injury (see fracture handbook). Sometimes if the injury is still unclear an ultrasound scan (as used for pregnant women) or an MRI scan may be requested. Generally the ligaments are too small to show well on scans.

Other tests such as a CT scan may be ordered to assess the bones and joints if there are concerns about associated injuries at the same site.

MRI scan: An MRI scanner is usually a short tunnel which the patient’s arms and top half of the body go into. Usually the arms are stretched out in a “superman” pose which is a little uncomfortable but generally well tolerated. Once in the tunnel a loud magnet is spun around and images of the bones and soft tissues created. Some people find the tunnel rather claustrophobic. If any patient doubts whether they would tolerate the scan they are best advised to visit the scanner department in advance. The films will be reported by a radiologist but also reviewed by the Hand specialist who will advise the patient accordingly.

CT scan: A CT (or CAT) scanner is a short large open tunnel. The patient lies on a bed and passes through the tunnel whilst X-rays are shone from various directions at the area of the body being investigated. It is particularly useful for showing bone abnormalities but less good at investigating soft tissue problems. The films will be reported by a radiologist but also reviewed by the Hand specialist who will advise the patient accordingly.

What treatment is needed?

Most ligament injuries are treated by the patient or their family at home rest, pain relief and gentle movement from there with good results.

For complete tears particularly at specific joints a period of immobilisation in a plaster or splint may be necessary and in some cases open surgical repair is needed (see details below).

Hand:

The small joints of the fingers (PIP and DIP joints) are naturally very stable and rarely need surgery unless there is also a fracture (see bone injuries). If very sore or unstable immobilisation in a splint or plaster initially full time for up to 2 weeks and then on and off for about 4 weeks is usually enough.

The larger finger joints (MP joints – at the junction of the fingers and palm) are naturally less stable so more dependent upon their ligament supports. There is controversy over their treatment but research we have undertaken has shown that most of these injuries do very well with strapping to the neighbouring finger for 3-6 weeks and free movement from there.

The end joint of the thumb (IP joint) is like the small joints of the fingers and can be treated the same way with initial full-time support and then part-time support up to about 4 weeks from injury.

The middle joint of the thumb (MP joint – at the junction of the thumb and palm) has important ligaments on both sides (the radial – outer side, and the ulnar – inner side). Because of local differences in the alignment of the soft tissues the radial (outer) ligament tears are treated differently to those on the inner side:

The outer ligament tears almost all heal well with 4 weeks of full time protection typically in a plaster. The inner ligaments often do not heal well without surgery unless there is a small local fracture of the bone where the ligament had attached. The injuries with fractures can usually be treated with 4 weeks of full time immobilisation in plaster. The injuries with no fracture usually need open surgery to confirm the diagnosis and perform a repair. This is usually supported in a plaster or splint for about 4 weeks.

The inner ligament tears would also heal as well but the tendon of another muscle can get in the way of the healing ligament preventing healing. This leads to considerable weakness in the thumb. Because of this open (surgical) assessment of the ligament is recommended usually with repair of the tear. The tear may be repaired in a variety of ways including stitching to the local soft tissues or bone (thumb proximal phalanx) or fixing it with stitches connected to anchors in the bone. Depending upon the severity of the repair the MP joint will be supported. This is almost always with a plaster or splint for 4 weeks and sometimes with a wire placed across the joint at the time of surgery. The wire is removed in the outpatient’s clinic after 4 weeks or so.

The ligaments holding bottom (near) joint of the thumb (CMC joint) are very important in stabilising the joint to ensure normal function and prevent risks of long-term arthritis. Injuries at this joint are usually associated with small fracture of the base of the thumb metacarpal bone known as a Bennett’s fracture (see fracture handbook). Rarely there is a true ligament injury with no bone injury. The treatment of both injuries is the same. The joint needs to be held reduced for 5-6 weeks. This cannot be done successfully in plaster. Rather formal surgical reduction and wiring under a local (sometimes general) anaesthetic is needed. The one or two wires are supported in plaster for 5-6 weeks when the wire(s) are removed in the outpatient’s clinic.

Wrist:

Wrist ligament injuries are very complex as the wrist is much the most complex joint of the body. Often they follow a fall and are associated with fractures of the wrist bones. If these are treated correctly then many of the ligament injuries will settle reasonably well. Injuries to the ligaments alone and not to the wrist bones are becoming more commonly recognised. Fortunately many can be successfully treated for up to 3 months from injury so delay in diagnosis and treatment is less serious. The diagnosis will be suggested by the nature of the injury (e.g. a high energy fall such as from a height or at speed e.g. falling off a bike) and examination of the wrist especially if performed by a Hand specialist. X-rays are the first test. They may show malalignment of the wrist bones but are often normal especially early following injury. The next test would generally be an MRI scan (see above) with or without an injection of a special dye to help show up ligament injuries. Even then the extent of the injuries can be unclear. This is best confirmed by keyhole surgery looking inside the wrist to assess the ligaments. This does however require an anaesthetic and cuts of the skin. If significant ligament injuries are found these can be repaired either by opening up the wrist or increasingly by holding the bones together with wires or screws to allow the ligaments to heal on their own in an optimal position. Early repair is preferable as late reconstruction of wrist ligament injuries is at present inconsistent. Typically the screws/wires will remain in the wrist for 8-12 weeks. During this time the wrist is held in a plaster or splint. The screws/wires will need to be removed in the operating theatre under anaesthetic as a day-case.

Elbow:

Elbow ligament injuries are complex as the elbow is a very constrained joint that takes a lot of weight on lifting and is very dependent upon stable ligaments. The ligaments around the elbow are typically injured following a fall when the elbow dislocates sometimes with fractures. The diagnosis will be suggested by the nature of the injury (e.g. a high energy fall such as from a height or at speed e.g. falling off a bike) and examination of the elbow especially if performed by a Hand or Elbow specialist. X-rays are the first test. They may show malalignment of the elbow bones particularly after a dislocation but further X-rays taken when the elbow has been put back are often normal. Usually the joint can be reduced in the Accident and Emergency (A & E) department under sedation. The elbow is held in plaster or a splint for about 2 weeks and then the elbow can be allowed to move assisted by therapists. In most cases the ligaments heal without significant problems although some stiffness. If there is a fracture as well as a dislocation then surgery to fix the fracture may also be required. Only infrequently is ligament repair needed.

What happens in the next few weeks?

The care of the hand in the post-injury/post-operative period is very important in helping to ensure a good result. Initially the aims are comfort and elevation.

Comfort and elevation: These are met by keeping the hand up (elevated) especially in the first few days and by use of a long acting local anaesthetic (Bupivicaine) if the hand/wrist/elbow has been operated upon. The local anaesthetic lasts at least 12 hours and sometimes 48 hours. Patients should start taking painkillers before the pain starts i.e. on return home and for at least 24 hours from there. This way most of our patients report little or any pain.

Dressings: Ligament injuries tend to need either careful early movement or protection for 4-6 weeks as noted above.

Movement: Most joint movement should be regained gained following treatment even surgery. Most movement occurs in the first 6-12 weeks and this time must be used productively to ensure a good result. The key is regular long gentle stretches both into straightening and into bending. Ideally these should be performed for 5 mins in each direction (feeling the stretch but without pain) once an hour. In practical terms most people manage to stretch 5-6 times a day. Elevation and icing the elbow also help reduce swelling and thus pain and improve movement.

Wound massage: The wound(s) should be massaged by the patient 3 times a day with a bland soft cream for 3 months once the wound is well healed (typically after 2 weeks, or after 4-6 weeks if protected in plaster). This reduces the scar sensitivity which can be a nuisance. If this is marked hand therapy may be organised to help reduce the scar tenderness but this is rarely required. Patients should avoid pressing heavily on the scar for 3 months following the operation as this will be quite painful. Examples of activities to avoid are using the palm to grip/twist a heavy or tight object or use the palm to help get out of a chair.

Return to daily activities: The hand can be used for normal activity after the first few days for mild injuries but obviously not whilst in plaster. Most patients can drive after a few days following a mild injury or after coming out of plaster. Most patients return to work immediately or in days following mild injuries but this varies with occupation; return to heavy manual work may take up to 2-4 weeks even for mild injuries and typically 6 weeks or so following surgery. The treating team should advise about this.

What are the results of treatment?

Most patients heal without significant problems especially for mild injuries. For more severe injuries particularly if surgery is required then full recovery is infrequent. In the arm and hand the term “functional range of movement” is widely used. This means a range of movement adequate for 90% of daily activities (assuming the other joints are normal). For each of the elbow, wrist and hand the ranges for good function are typically:

Elbow – 30–1200 i.e. nearly but not fully straight by 300 and bending well but not fully. The normal range of movement is 0-1400

Forearm – 45-450 i.e. just over half of normal movement. The normal range is supination (turning the palm up) 800 and pronation (turning the palm down) 750

Wrist – Extension (cocking the wrist back) 300 and flexion (bending the wrist down) 100. This is around 25% of normal movement which is extension of 800 and flexion of 800

Thumb

MP joint – Fixed flexion deformity of 100 and flexion to 300. Normally the range is very variable between individuals. Stiffness in this joint is well tolerated if the joint is painless and stable.

IP joint – Fixed flexion deformity of 100 and flexion to 300. Normally the range is very variable between individuals. Stiffness in this joint, like the MP joint is well tolerated if the joint is painless and stable.

Fingers

MP joint – Fixed flexion deformity of 100 and flexion to 400. Normally the range is 0-900. Stiffness in this joint is better tolerated than in the PIP joint (see below). In general loss of flexion (bending) is better tolerated than loss of extension (straightening).

PIP joint – Fixed flexion deformity of 300 and flexion to 800. Movement in the PIP joints is very important and stiffness is not well tolerated. The normal range of movement is 0-1100

DIP joint – Fixed flexion deformity of 100 and flexion to 300. Normally the range is 0-700. Stiffness in this joint, like the IP joint of the thumb is well tolerated if the joint is painless and stable.

Most of these ranges are achieved but not always especially with injuries to multiple tendons, injuries to the bending tendons in the fingers and combined injuries such as tendon as well as nerve/bone/artery injuries. Most patients have long-term aching in the cold but this may improve for up to 3-4 years from injury and in usually not too marked. Secondary reconstructive surgery is required infrequently in our experience. It is more common in patients with complex open injuries or those who attend late i.e. after 4-6 weeks from injury.

Are there any risks from surgery?

All interventions in medicine have risks. In general the bigger the operation the greater the risks. With injuries the outcome is mainly due to the severity of the initial injury. For skin grafting or flaps the risks include:

- The scar may be tender, in about 20% of patients. This usually improves with scar massage, over 3 months.

- Aching at the site may last for several months

- Grip strength can also take some months to return to normal.

- Stiffness may occur in particular in the fingers.

- Numbness can occur around the scar but this rarely causes any functional problems.

- Wound infections occur in about 1-5% of cases. These usually quickly resolve with antibiotics.

- Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome “CRPS”. This is a rare but serious complication, with no known cause or proven treatment. The nerves in the hand “over-react”, causing swelling, pain, discolouration and stiffness, which improve very slowly.

- Any operation can have unforeseen consequences and leave a patient worse than before surgery.